The Global Value Scorecard – A Strategic Response to Cross-Border Uncertainties

“Sensing a delicate change in the seasons

You savor the world, and you are opened.”

- William Ayot

Global businesses have a huge impact on nations and communities across the world. These businesses are large and complex, and as such they require special, and often new techniques, tools and management skills to operate successfully. Indeed, a typical international business can be viewed as a system of systems. The interactions of its subsystems are complex and dynamic, with numerous interdependencies at different institutional, regulative, cultural and subcultural levels. That is why it is challenging to conduct a feasibility study of alternatives: i.e., an evaluation of pros and cons and business case estimations. It is not a straightforward approach, as many unknown factors may cause significant deviation.

It is also difficult to plan for cross-border moves because the time horizons are typically long. Lessening the risks of planning fallacies, strategic misrepresentation, principal-agent problems and rent seeking behaviour becomes critical as the business footprint grows. Likewise, political, technological, economic and aesthetic factors affect all aspects of the global business life cycle. But cross-institutional and socio-political complexities do not necessarily increase the risk of business failure. On the contrary, the number of international businesses has exploded since the globalisation era began. In that way leaders have been unlocking new opportunities through global expansions and multinational partnerships with cross-border institutions. These emerging opportunities have brought distinctive strategic value through 1) labour arbitrage 2) currency and compliance risk hedging 3) access to unique resources and services, including manpower and 4) access to know-how. This article explores two main questions: 1) Why do global businesses fail? 2) How can such failures be prevented?

Levitt and Scott (2017) defined a global project “… as a temporary endeavour where multiple actors seek to optimize outcomes by combining resources from multiple sites, organizations, cultures, and geographies through a combination of contractual, hierarchical, and network-based modes of organization.” Business failures are treated in terms of cost overruns, schedule delays, and benefit shortfalls -- expressed as product or service performance -- compared to the plan. As Taleb (2012) notes, “…globalization brings fragilities, causes more extreme events as a side effect, and requires a great deal of redundancies to operate properly.” Further, Van Marrewijk et al. (2008) argue that cross-border failures are caused by involving a large number of stakeholders with diverse cultures and different approaches to problem solving. Chipman (2016) borrows governmental language to describe the necessary course of action: “A corporate foreign policy has two components. Geopolitical due diligence involves the assessment of local, regional, and transnational risks facing a company. Corporate diplomacy aims to enhance a company’s ability to operate internationally and to ensure its success in each particular country with which it is engaged.” In other words, proper corporate governance minimises the risk of cross-border moves.

Flyvbjerg (2006, 2012) makes a different argument, asserting that leaders should address psychological-optimism bias, strategic misinterpretation and incentives, in order to minimise the risk of global business failure. Krugman, Obstfeld and Melitz (2015) also support this idea, arguing that global businesses typically suffer from a variety of biases.

To minimise the risk of global business failure, leaders must not only address problems of cost and schedule underestimations but also address human bias. The findings of behavioural scientists can help global businesses do exactly that. For example, Thaler and Sunstein (2009) argue that, “Unrealistic optimism is a pervasive feature of human life; it characterizes most people in most social categories.” When leaders optimistically imagine that cross-border business will be immune from such failure, they fail to take sensible preventive actions to manage global multi-actor interfaces. As Kahneman (2012) observes, “most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our own attributes as more favourable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be”. In other words, overconfidence bias is a normal element of human mentality and daily life. Acknowledging that fact, however, can help leaders steer global business in a way that removes such biases from decision-making - and as a result, minimises the risks of planning fallacies and strategic misrepresentation. Ultimately, understanding human bias aligns the conflicting interests of international stakeholders and helps business leaders manage the complexities of their involvement. As Taleb (2012) explains, “we can certainly attribute the fragility effect of contemporary globalization to complexity, and how connectivity and cultural contagions make gyrations in economic variables much more severe…”. Thus, in order to minimise the risks of cross-border moves, leaders should address the root causes of business failures: 1) removing bias from feasibility studies and business case estimations 2) designing a proper incentive matrix and 3) employing a team of professionals with a proven track of successfully executed cross-border moves.

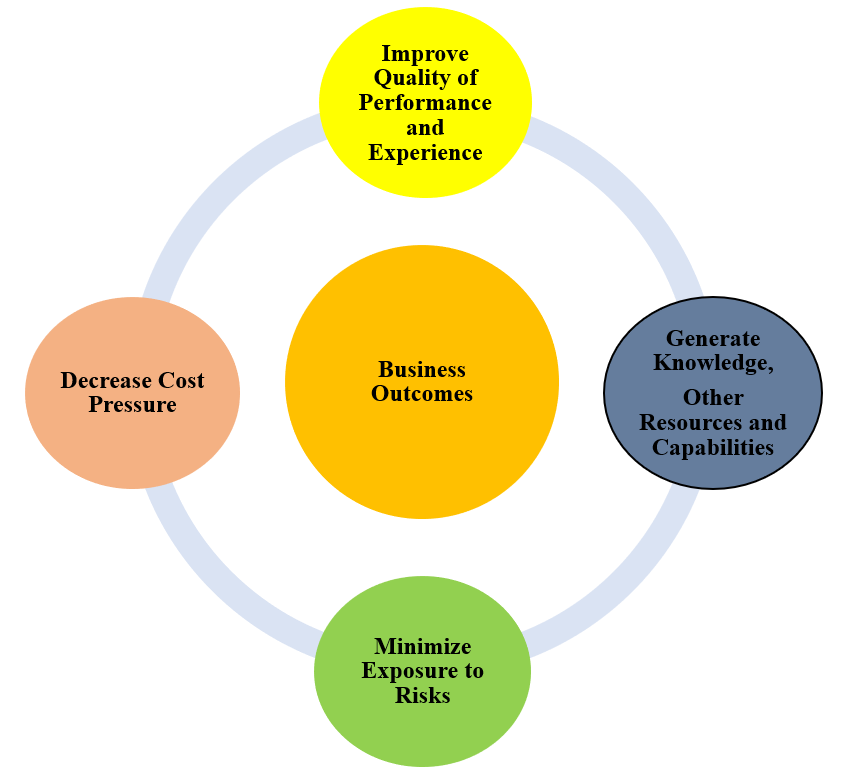

Based upon empirical evidence, we propose a global value scorecard. The scorecard helps leaders: 1) improve quality of performance and experience 2) generate knowledge, other resources and capabilities 3) minimize exposure to risks 4) decrease cost pressure. Employing four global value components in addition to the proper governance framework enables leaders to create significant cross-border value. Understanding these global value components deeply helps leaders manage the uncertainty of irrational multicultural environments; it also lessens the risk associated with delusional optimism and planning fallacies. However, as Flyvbjerg (2017) observed, “Rationality cannot provide the ultimate warrant for project performativity.”

Ghemawat provides another important caveat: “Of course, that isn’t to say that all components are equally important in all industries or for all companies. Furthermore, different value components can become more or less important at different points in a company’s history.” The following figure provides an example of such a global value scorecard, which can serve as a strategic map to steer businesses internationally.

Figure 1

The Global Value Scorecard (inspired by Ghemawat (2007).

Our initial questions were these: Why do global businesses fail? And how can such failures be prevented? It is undeniable that cross-border expansions bring many benefits such as 1) labour arbitrage 2) currency risk hedging 3) access to unique resources and services 4) access to manpower and know-how and 5) reduced cost of capital. But the uncertainty of cross-border moves also creates critical challenges-and the risk of failure. Global strategy brings fragility associated with different cultures, subcultures, regulatory frameworks and conflicting stakeholders’ expectations. However, these alone do not cause global leadership failures. The most fundamental difficulties global businesses face are understanding irrational human behaviour, heuristic and bias. Addressing these root causes is critical to success in cross-border expansions.

References

Chipman J. (2016) ‘Why Your Company Needs a Foreign Policy’, Harvard Business Review.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2017) (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Megaproject Management, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flyvbjerg, B., (2006) From Nobel prize to project management: getting risk right. Proj. Manag. J. 37 (3), 5–15.

Flyvbjerg, B., (2012) Quality control and due diligence in project management: getting decisions right by taking the outside view. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 31 (5), 760–774.

Ghemawat, P. (2007) Redefining global strategy : Crossing borders in a world where differences still matter. Harvard Business Review.

Kahneman, D. (2012) Thinking, Fast and Slow (Great Britain: Penguin Books).

Krugman, P., Obstfeld M., Melitz M. (2015) International Economics: Theory and Policy. (US: Pearson Education).

Levitt, R. and Scott, R (2017) Institutional Challenges and Solutions for Global Megaprojects. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taleb, N. (2010) The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable, 2nd ed., (New York: Random House).

Taleb, N. (2012) Anti-fragile: Things that Gain from Disorder (New York: Random House).

Thaler R., Sunstein C. (2008) Nudge: Improving decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (the United States of America).

Van Marrewijk, A., Clegg, S.R., Pitsis, T.S., Veenswijk, M., (2008) Managing public–private megaprojects: paradoxes, complexity, and project design. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 26 (8), 591–600.